Random Political Joke - Politicians don’t lie. They just run limited-time truth promotions.

Egypt

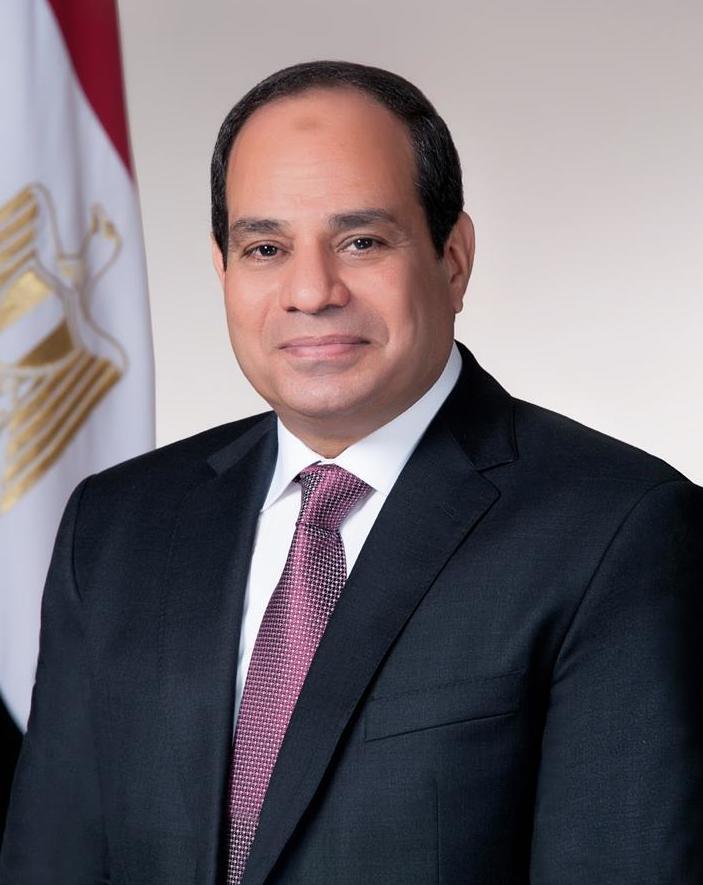

Presient السيسي عبد الفتاح (Abdel Fattah el-Sisi)

Impeachment Estimate

Updated: 2026-01-06

Model Risk: 5%

Public Impeachment Search Heat: 0%

Regime Risk: 25% ? Regime Risk is completely separate from the impeachment estimate and is not used to calculate it. Regime Risk is an assessment of the overall stability of the current government regime, based on factors such as political unrest, economic instability, and social tensions. A high Regime Risk indicates a greater likelihood of significant political upheaval, which could lead to changes in leadership through means other than formal impeachment processes.

30-Day Impeachment Trend

30-Day Regime Risk Trend

Latest News

Egypt’s president meets Saudi foreign minister amid Yemen escalation - Middle East Monitor

UK won’t deport Egyptian man who praised killing ‘Zionists’ - JNS.org

Egypt’s President Meets Saudi Foreign Minister as Yemen Tensions Escalate - The Voice of Africa

Quick Summary of Egypt & Abdel Fattah el-Sisi

Egypt has not experienced formal impeachment proceedings against its leaders in modern history, and President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi remains firmly in power with little domestic or international pressure to remove him through such mechanisms. As a former military general who took office in 2014 following a coup that ousted President Mohamed Morsi, el-Sisi has consolidated authority through constitutional amendments, crackdowns on dissent, and a tightly controlled political system. While criticism of his government exists,particularly regarding human rights abuses, economic struggles, and restrictions on free speech,no credible movement or legal framework currently exists to challenge his presidency through impeachment. The Egyptian constitution does allow for the removal of a president under specific conditions, such as treason or criminal violations, but these provisions are effectively unenforceable under the current political climate. Internationally, el-Sisi’s government has faced scrutiny from human rights organizations and some Western governments, but this has not translated into calls for his removal. The United States and European Union have occasionally expressed concerns over Egypt’s democratic backsliding, yet strategic interests,such as regional stability, counterterrorism cooperation, and the Suez Canal,often take precedence in diplomatic relations. Domestically, opposition figures and activists who might push for accountability are frequently suppressed, leaving little room for organized resistance. While economic hardships and public discontent have sparked sporadic protests, el-Sisi’s administration has responded with swift repression, ensuring that any discussion of impeachment remains purely hypothetical. For now, his leadership appears secure, with no imminent threat to his position through legal or political means.Deep Dive Into Egypt & Abdel Fattah el-Sisi

Impeachment Color Legend

RED >= 50%ORANGE >= 34%

YELLOW >= 18%

GREEN < 18%